Imagine setting out on a 3,000-kilometer journey across China with just 1,000 yuan (~A$200), a tent, and a bold idea: hitchhike from Nanjing to Urumqi, revealing your Japanese identity to every driver who offers a ride. That’s exactly what Tanikawa Hibiki, a master’s student at Nanjing University, did during his 2025 winter vacation. His 21-day odyssey, shared via Beijing Scroll and Bindian Weekly, wasn’t just a travel adventure—it was a heartfelt social experiment exploring human kindness across cultural divides. As a travel enthusiast, I’m thrilled to dive into Tanikawa’s story, a vibrant tapestry of China’s landscapes, grassroots culture, and the generosity of strangers.

The Journey Begins: Nanjing to the Unknown

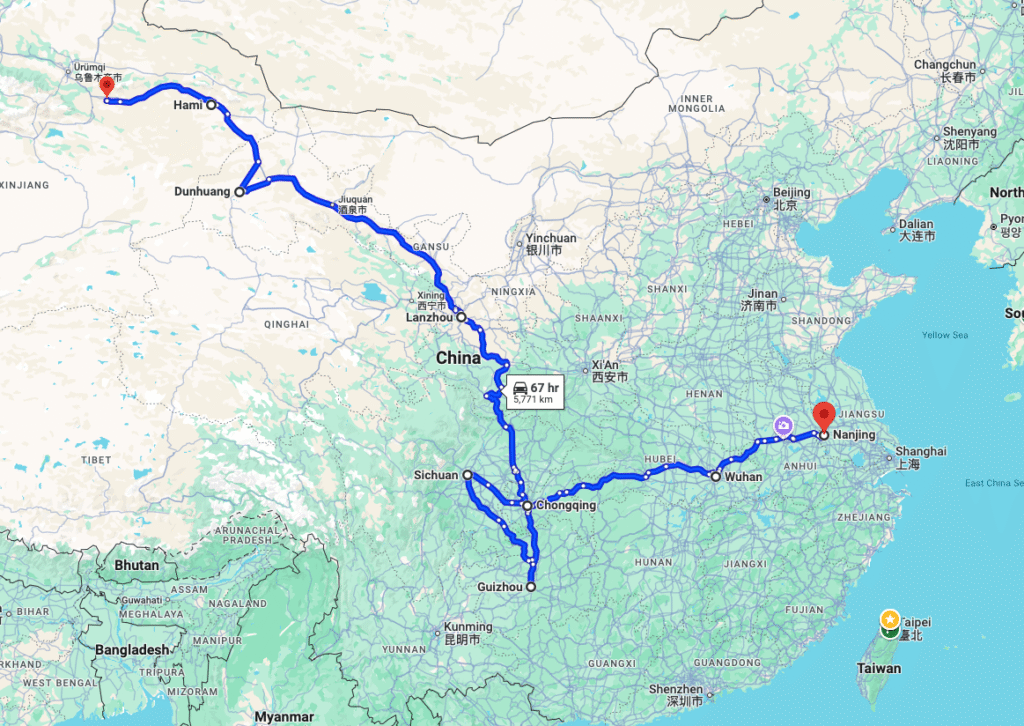

Tanikawa’s adventure kicked off on January 21, 2025, at Nanjing University’s south gate. Armed with a suitcase stuffed with a 239-yuan tent, a sleeping bag, and warm clothes for Urumqi’s -20°C chill, he planned a route through Wuhan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Lanzhou, Dunhuang, Hami, and Turpan. With limited funds, hitchhiking was his ticket to explore China’s heart—not just its geography but its people. His “social experiment” was simple yet daring: ask drivers for a ride, then disclose he’s Japanese to see if they’d still help. This personal quest, rooted in curiosity about a nation historically complex with Japan, set the stage for a transformative journey.

His first ride came from a Nanjing gas station worker who admired Tanikawa’s dream of roaming China. “I used to have dreams like yours,” the young man said, driving him to Baguazhou Service Area. That first night, Tanikawa camped in his tent, marveling at the clean, spacious highway service areas—a far cry from what he’d expected. Early challenges tested his resolve: freezing nights, a bout of fever and diarrhea in Taihe, Anhui, and the unpredictability of finding rides. Yet, each hurdle revealed China’s warmth, like the locals in Taihe who welcomed him during Spring Festival, evoking the family-centric vibe he’d seen in the sitcom Home with Kids.

Cultural Immersion: Spring Festival in Luoyang

Arriving in Luoyang, Tanikawa experienced his first Chinese New Year. Staying with a friend, he joined a family for New Year’s Eve, visited relatives, and received his first hongbao (red envelope)—a moment of cultural connection that felt both novel and heartwarming. Exploring the Longmen Grottoes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, he felt a “karmic connection” to the ancient Buddhist statues, echoing his own Buddhist school background in Japan. At White Horse Temple, he witnessed families praying together, underscoring Spring Festival’s role as a cultural and spiritual anchor. These moments painted a picture of China’s grassroots society—complex, warm, and deeply familial.

Westward Bound: From Xi’an to the Gobi

As Tanikawa ventured west, China’s diversity unfolded. In Xi’an, he queued for hours to see the Terracotta Warriors and camped by the Weihe Wetland Park, lulled by birdsong. Lanzhou dazzled with its Yellow River waterwheels, Zhongshan Bridge, and snow-capped mountains that shattered his stereotypes of northern Chinese cities. A stranger paid his bus fare, and a shopkeeper safeguarded his luggage, leaving a note when she took it to a police station. These small acts of kindness became the heartbeat of his journey.

The northwest brought new challenges: -17°C nights at high-altitude Tibetan-influenced service areas like Anmen, where vibrant architecture and script signaled a cultural shift. Standing before the 4,447-meter Mayashan Mountain, Tanikawa was awestruck, likening it to Mount Fuji’s majesty. In the Gobi Desert, the “Son of the Earth” sculpture—a solitary figure in a vast, arid expanse—spoke to resilience. Here, he encountered camel thorn, a brittle plant that underscored the desert’s harsh beauty.

The Social Experiment: Kindness Over Prejudice

The core of Tanikawa’s journey was his social experiment. Of the 17 drivers who agreed to give him a ride, only one refused after learning he was Japanese—a 94.1% acceptance rate. A standout moment came with a driver who admitted, “I hate Japan,” yet gave him a ride, saying, “Helping others is my habit.” This encounter reshaped Tanikawa’s view of kindness, showing it could transcend personal biases. Other drivers—a migrant couple, an international duo, a young art teacher—shared stories of unfulfilled dreams, inspired by Tanikawa’s courage. Each ride was a window into China’s soul, from rural simplicity to urban ambition.

The Final Stretch: Urumqi and Reflections

On February 11, Tanikawa reached Urumqi’s Sanping Service Area at 12:57 AM. Expecting tears, he felt calm instead, his heart full from experiences like enduring snow nights, losing and recovering belongings, and meeting kind strangers. Staying with an ethnic minority friend for three days, he immersed himself in Xinjiang’s vibrant culture—mutton barbecues, naan, and a surreal snow rainbow. His 56-hour train ride back to Nanjing, standing ticket in hand, replayed the journey like a movie, cementing memories of cities and faces.

Why This Matters for Travelers

Tanikawa’s odyssey is a love letter to immersive travel. It reminds us that journeys are as much about people as places. His story, echoing the adventures of readers like Dr. Carl Lee and Liz Hardie, inspires us to step into the unknown, engage with locals, and embrace cultural complexities. For travelers, China’s grassroots society—its service areas, festivals, and desert sculptures—offers a raw, textured reality. Tanikawa’s experiment proves that kindness often bridges divides, making hitchhiking a powerful way to connect with a nation’s heart.

Follow Tanikawa’s journey and more at Beijing Scroll. Let this story inspire your next adventure!